Stories as Soft-Spoken Warnings: Mourning, Disappearance, & the Thin Places Where Women Have Come to Dwell in Cynthia Pelayo's "Vanishing Daughters"

"Death is such a difficult opponent to fight." pg. 119

I inevitably run the risk of sounding like a broken record whenever I review Cynthia Pelayo’s staggering body of work. Perhaps it’s due to Cina and I having several shared special interest topics—the main ones being horror, fairytales, and the ways the two enmesh—or I simply repeat myself a lot, however, that’s for y’all to judge.

In a time that feels like forever ago, I did an in-depth review of Pelayo’s 2024 novel, Forgotten Sisters, which took a look at the spiritually-connected Chicago Trilogy that concluded, in a sense, with Forgotten Sisters. This was a way of celebrating the string of fantastically haunting novels, as well as highlighting the brilliance of her web of tales and how they extend outside of singular novels.

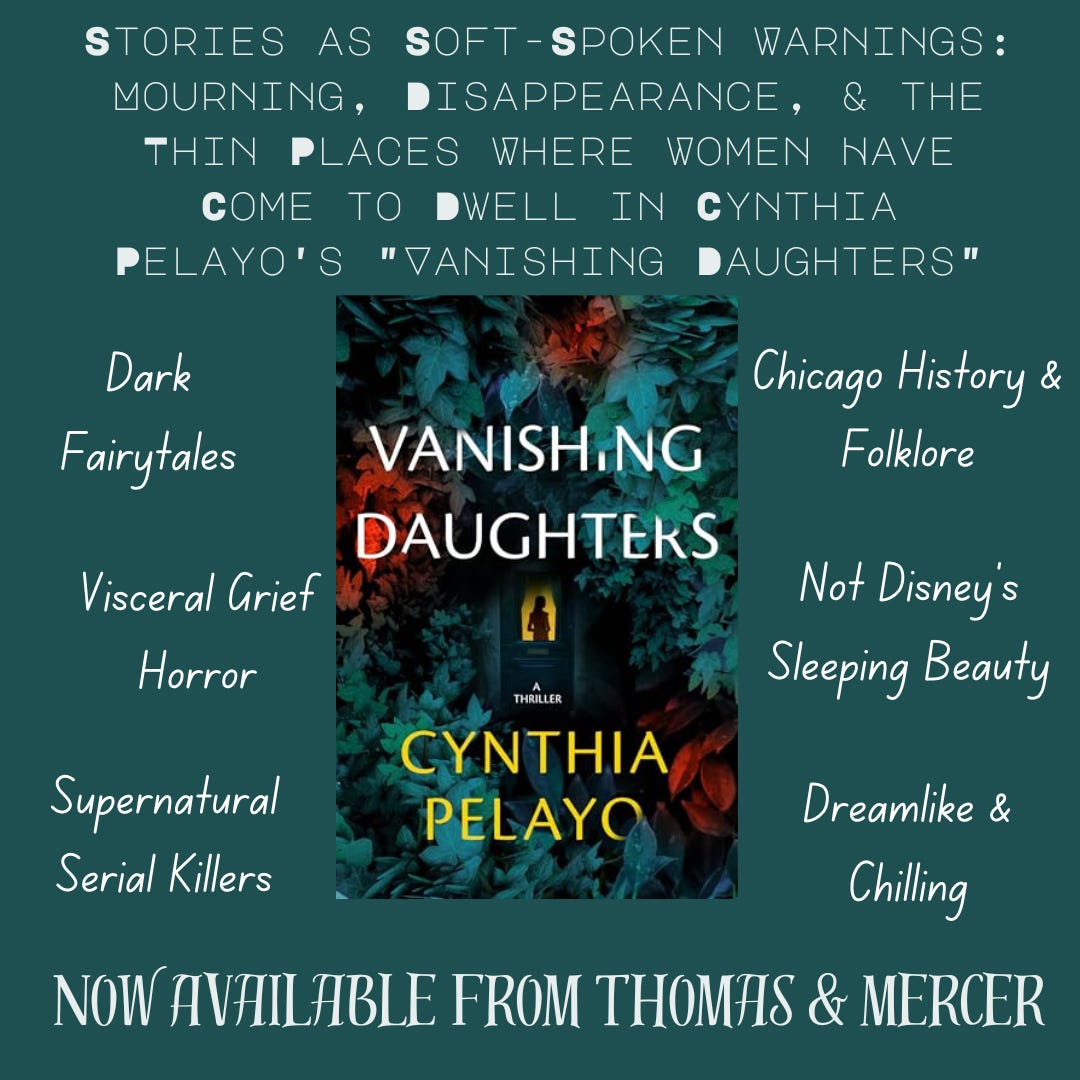

2025 sees the upcoming release of Pelayo’s next novel, Vanishing Daughters, which will be the focus of today’s piece. Unsurprisingly, this thriller additionally shares DNA with not only its predecessor, but her Stoker Award nominated speculative poetry collection Into the Forest and All the Way Through as well. Therefore, yet again, my comparative literature brain is going to draw connections and highlight what may be the author’s best work to date.

Yeah, I said it. Will I say it again when another book comes out? Probably. What do you want from me?? She’s great, and only getting better.

Into the Forest and All the Way Through, and Our Neverending Search for Lost Women

It’s no surprise the United States hates women. From our puritanical roots to the current onslaught of evangelical christianity attempting to take over everything to fulfill their patriarchal, white supremacist, deathwish dreams, women and fems have been within the crosshairs of just about every social issue from the beginning of our decaying country. I could go on about colonialism and how this is a massive European and American issue, but, again—broken record.

All of this becomes sevenfold when factoring in the thousands of disappearances and deaths of Indigenous, Black, Asian & Pacific Islander, South Asian, Trans, and many other women and femmes. In a country simultaneously obsessed with true crime but holding no real desire to do much about any of it, we hear of these cases constantly (if you follow a news source that actually covers these things). These topics have shown up in just about all of Pelayo’s work, but Into the Forest was the first time we saw these themes in full force.

Over the course of the collection’s dark descent into a slew of heartbreaking missing cases, Pelayo highlights just how large of an issue this is, using her speculative voice to emphasize the emotions, fear, class disparity, and so much more responsible for these cases. As the author informs us at the end, many of these cases are still open and weep to be solved.

Many of these themes appear throughout her work, but it’s her distillations of grief and sibling/familial loss that strikes to the heart of these issues, detailing the damage and trauma left in the wake of these disappearances/deaths. While we’ll be getting into more of this later, the theme is present throughout Into the Forest, and is prevalent throughout Vanishing Daughters.

One of the novel’s two narrators, Briar Rose, has recently lost her mother, destabilizing her life in ways she never could have imagined. Inheriting the family home, nestled in Chicago near some of the most supernaturally charged areas known to the city, she’s experiencing horrifically cryptic dreams, strange men are standing outside of her house, the radios throughout will randomly turn on and react to her moods. While these horror elements serve to push the plot forward and elucidate its folkloric influences, Pelayo’s poetic writing allows for these devices to highlight how hard trauma can ravage the body, especially when it comes to sleep and general functioning.

Navigating the poems in Crime Scene, you feel the palpable unease, grief, and uncanny dread manifested through her dark fairytales. The poems are centered around true stories, and with her background in journalism and love of history, Pelayo goes deep in bringing this roiling cauldron to a hearty and delicious concoction. Vanishing Daughters, and it’s predecessor of Forgotten Sisters, are similarly built from true events and stories whose crimes either go unsolved or are grossly underreported. Where some authors have utilized true crime cases in somewhat exploitative ways, Pelayo uses her interests in folklore, fairytales, and the horror (and beauty) inherent in our world to highlight the humanity prevalent in these cases and the people they inhabit/effect.

From Forgotten to Vanshing, or, What Modern Adaptations of Fairytale Heroines Tell Us About How We View Victims & Victimization

Pelayo is the perfect author for my autism, not only because her output allows me a wealth of works to pour over whenever the special interest hits, but she’s also someone who clearly has special interests and researches like a beast. When I learned she too had worked in journalism for a bit, it made perfect sense to me, as it appears she hungers for information just as I do. I promise, this is in part reinforced by conversations we’ve had!

Forgotten Sisters not only pulled from the folklore surrounding Hans Christian Anderson’s popular telling of The Little Mermaid, but also highlighted a great aquatic tragedy that took place in Chicago in 1915: the capsizing of the S.S. Easton. For Vanishing Daughters, Pelayo approaches another infamous urban legend, that of Resurrection Mary, herself known as a “vanishing hitchhiker.” This folklore trope has endured throughout American history, with plenty of motorists telling the tale of a mysterious hitchhiker that once passing the place of their grave or disappearance, vanishes without a trace. Or maybe a trace or two.

It wouldn’t be a Cina book without some fairytale connections, so Vanishing Daughters approaches the story of Sleeping Beauty—mainly the non-Disney iterations—providing a chilling recontextualization of the legends and how they connect to the wider folklore of Chicago as well. Our antagonist, aside from grief, is a stranger we never learn the true name of but exists as a member of a long line of supernatural serial killers. He is who finds his “beauties” and murders them so that they may sleep peacefully in his dream world. Obviously no one is sleeping peacefully there. His presence quickly poses an issue for Briar, however, as he feels particularly drawn to her. Oh, also it’s inferred this guy is H.H. Holmes’s son, which is pretty damn cool for nerds like me.

What becomes quickly evident is Briar’s story is somehow connected to Resurrection Mary’s disappearance and death. She’s plagued by nightmares surrounding Mary’s final night, while receiving cryptic messages from her mother’s spirit. As the story continues, we learn of the multiple connections between our understood fairytales and how they connect to this modern, speculative Chicago Pelayo brings to life. But why Resurrection Mary? Why the beloved Sleeping Beauty?

Much scholarship and cultural criticism has expounded upon our culture’s obsession with female or female-presenting victimization. Streaming platforms are constantly advertising their next true crime miniseries filled with people intimate to the crimes, as well as “experts” who claim to understand the nuances of the perpetrators, victims, and the emotions inherent in all of it. An example I constantly return to is Netflix’s bizarre miniseries centered around the mysterious but tragic passing of Elisa Lam, Crime Scene: The Vanishing at the Cecil Hotel.

We are drawn to mysterious stories such as this. Given little context, our minds wander and scramble for either rational explanations or supernatural ones. I too was initially fascinated by this incident, having seen the elevator footage around the time of its release and holding my own speculations, yet very quickly relegated it to the back of my memory as an unfortunate tragedy. Many years later, during quarantine, I was watching TV with my partner and their then-roommates, and we found the Netflix documentary and decided to start watching. What started as a fascinating search into the mystery itself morphed into a nightmarish series of speculations and deeply concerning parasocial behaviors from several of the interviewees. This was not a documentary series based solely around truth, but wanted its shock-factor cake to eat too. It broke my heart to see a young woman’s life, personality, and horrific tragedy reduced to revenue. But this is so common.

Why are we obsessed with the pain of the marginalized? Its obvious this content sells, as every month there is a glut of documentaries, miniseries, podcasts, and books surrounding true crime cases. Our religious roots certainly could trace a thru-line, as we are a deeply sexually repressed society, but one also terrified of death. Where some cultures view death as a multi-faceted experience of grief, celebration, and much more, western beliefs often focus solely on the grief, while never entirely offering its people the time, resources, or care to properly grieve when the time comes. In part, I think this is where our fascination with the supernatural comes in. We long for possibilities where we can see our loved ones again.

Whether its Elisa Lam, the victims of infamous serial killers, or Resurrection Mary, it’s clear we’re drawn to the pain of women and fem-presenting individuals. Is it guilt, from the ways we treat women as a society? Do we feel a sense of moral absolve if we focus on “solving” these cases because we’re complicit in so much of these tragic incidents? Pelayo has always taken far more nuanced approaches to writing about these tragedies. In a way, she’s working to make sense of these legends and stories, weaving fairytale, urban legend, and history to make sense of such continued violence. Chicago being the epicenter it is, she’s able to point to its rich history to help modern day readers make sense of this epidemic of disappearance and destruction. Her Mary, Briar, and many of the other characters present here are provided stunning life and dimension as a means of reclaiming these narratives and people’s salacious speculations.

“I exist on the edges of fear and sorrow”: How We Grieve the Forgotten & Vanished

Before we conclude, I want to talk a bit about grief in Vanishing Daughters. The ways in which Pelayo perfectly captures the surreal and unmooring sensations often coupled with grieving is nothing short of extraordinary. While one could say grief is all she writes about, that’s never the point of what Cina sets out to achieve in her books. Plus, with her own personal struggles, these past few books have appeared as very necessary forms of grieving for her, yet, she also does so to reconfigure and reinforce how we as grieving creatures can, will, and perhaps should experience it.

Briar’s grief surrounding the passing of her mother takes up every aspect of her life. Similarly to Forgotten Sisters, much of what Briar experiences within her house is not only surreal and meant to keep us on our toes, but equally reflects just what it can feel or appear as throughout the process. She can’t sleep, can barely eat, tries to self medicate with coffee, but most importantly—isolates herself from her other loved ones, allowing the house to function as its own character.

This device has popped up a few times in the past few years, as authors have sought to reinvigorate the subgenre itself. Instead of the house as a site for scares, we find the character of the house creates its own amalgam of pain, sorrow, anger, revenge, etc. In Briar’s case, the house—as well as the spirits within it—is attempting to aide her in solving the mystery of Mary and her connection to the wider family. In this instance, the house is grieving alongside Briar, whether it’s randomly playing songs on any of the hundreds of radios collected inside, whispers, and other disruptions. Our heroine comes to recognize the houses own symptoms concurrently with her own.

By the end of the book, we’ve witnessed Briar grasp ahold of her agency, harnessing her grief as a way of not only stepping toe to toe with our serial killer, but healing in a way reflective of the “Acceptance” level of grieving as well. I won’t spoil the ending ending here because it’s best experienced yourself. Prepare at least four full boxes of tissues whenever you do. This one is a DOOZY, on par with the ending of Pelayo’s The Shoemaker’s Magician. Hers are depictions of grief with their own energy and power, which isn’t to say other writers fail to do this, but Cynthia Pelayo somehow brings an electric charge to the subject that subsumes you into the experience itself.

Conlusions, or, my final pitch for you to read this book!

And it’s now we must reach our conclusion! I do this to myself every single time, but it’s hard work for authors I truly love. Cynthia Pelayo was one of the first authors to get me back into the contemporary horror game with voracious earnest. She is a remarkable spirit with so much care, love, and patience within her, and it’s my firm belief she puts all of this into her books as well. Even the scariest villain becomes expansive under her pen, offering empathetic approaches to even fairly irredeemable characters. It’s simply who Cynthia is.

Vanishing Daughters feels even stronger than Forgotten Sisters did, which is only indicative of Pelayo’s growing mastery as a writer. Between the books I previously mentioned, her ever-poetic prose, and the truly pulse-pounding action swiftly developing the central mystery and stakes, it sets Vanishing Daughters on track to join the great canon of horror thrillers. It feels like the obvious progression for someone currently standing amidst the greats of the genre. I have no idea what the next novel will be about, but I know I will dive in with glee because it’s a Cina book.

Immense appreciation to Thomas & Mercer, as well as my beloved Cina for an early copy of this incredible novel. It is now available wherever books are sold.